Writing HTTP files to test HTTP APIs

Writing automated tests for HTTP APIs is currently harder than it needs to be. You have basically two common approaches to the problem:

- write tests in your favourite programming language using a HTTP client.

- use a GUI tool like Postman, Swagger Inspector and its older cousin, SoapUI.

I believe that none of these approaches is ideal. Furthermore, I think that an alternative solution exists that is much better in most situations, but is still not very well-known: writing HTTP directly in a text file, with a few human-friendly conveniences added in order to make it a more pleasurable experience.

In this blog post, I will explain what I believe is the problem with the current approaches, and why HTTP files are a great alternative.

The problem with programmatic HTTP API tests

When you write tests in your favourite programming language, you have infinite flexibility. You can do basically anything you can imagine, so in terms of flexibility, programmatic tests are definitely the best choice.

But this is also the problem with programmatic tests: because they are so general purpose, they are harder to read and maintain. Depending on the complexity of the test, it may become almost impossible to even know what’s being tested.

This is very common and usually brings up the question: what’s testing the tests? Can you even be sure that a test failure is caused not by a bug in your API, but by a bug in the test?

Programmatic tests are also quite difficult to write. HTTP clients in most languages, for some reason, tend to be clunky and hard to work with. Just for a little taste, this is what most Java developers have to deal with:

class GitHubUser {

private String login;

// standard getters and setters

}

public class MyTest {

@Test

public void

givenUserExists_whenUserInformationIsRetrieved_thenRetrievedResourceIsCorrect()

throws ClientProtocolException, IOException {

// Given

HttpUriRequest request = new HttpGet( "https://api.github.com/users/eugenp" );

// When

HttpResponse response = HttpClientBuilder.create().build().execute( request );

// Then

GitHubUser resource = RetrieveUtil.retrieveResourceFromResponse(

response, GitHubUser.class);

assertThat( "eugenp", Matchers.is( resource.getLogin() ) );

}

public static <T> T retrieveResourceFromResponse(HttpResponse response, Class<T> clazz)

throws IOException {

String jsonFromResponse = EntityUtils.toString(response.getEntity());

ObjectMapper mapper = new ObjectMapper()

.configure(DeserializationFeature.FAIL_ON_UNKNOWN_PROPERTIES, false);

return mapper.readValue(jsonFromResponse, clazz);

}

}

The above example is taken from the excellent Baeldung website.

If you think this looks ok, please bear with me. This is absolutely not ok, and I hope to convince you soon that there are much better ways.

GUI-based testing tools

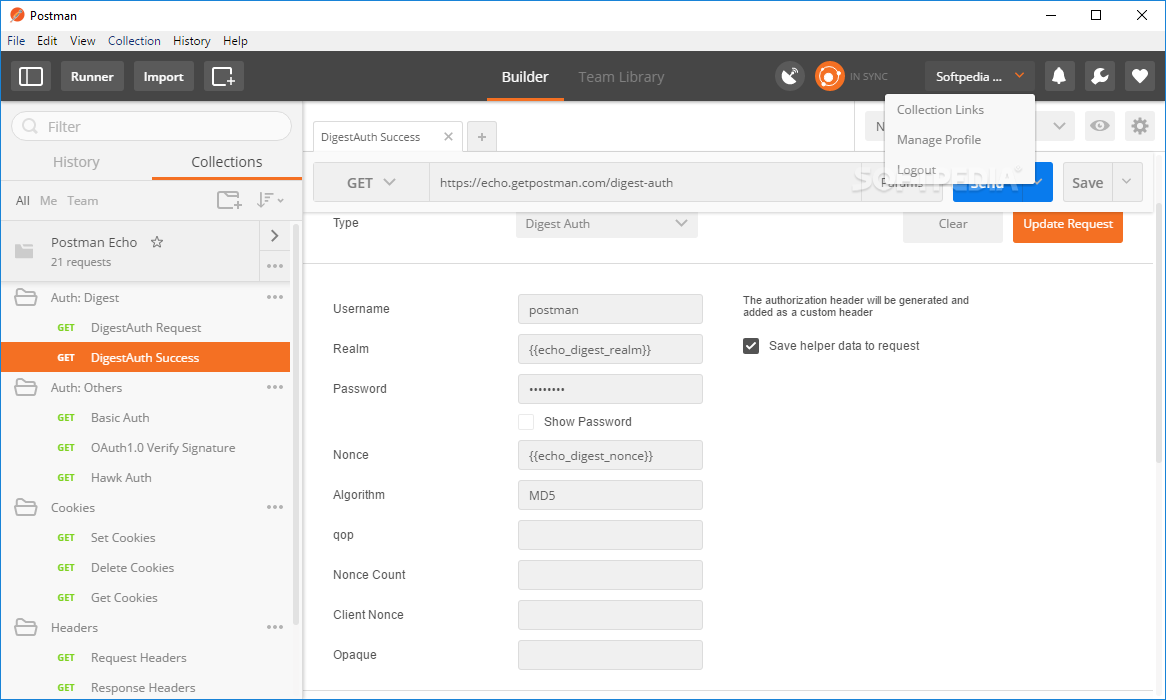

GUI-based testing tools mostly have the opposite problem of programmatic tests: instead of being too flexible, they are too constrained and can only do what the authors of the tool decided you might need.

They always try to abstract away “difficult” concepts from users, so you might have a little table with “parameters” when you’re composing a request. Are those query parameters? Or form parameters? Perhaps they are actually part of the JSON body? If you have someone testing your HTTP APIs who can’t tell the difference, you should probably consider if the testing they are going to do can be relied on.

These tools usually have support for “scripting” to overcome some of their limitations, but if you use that a lot, you just end up with the worst of both worlds: too much abstraction, but also too much hard-to-understand code that could be doing anything.

One last point against GUI-based tools is that they are difficult to integrate with your CI pipeline, and most of the time, are not free once you want to use them that way (or just need some key feature that is only available in the Pro version).

This makes them, in my opinion, great for exploratory testing… but not appropriate for automated tests that run in your CI (or as part of any test suite developers have to run often).

An alternative: HTTP files

A HTTP file is, in essence, a file where you write your HTTP requests by hand, and use some small code snippets to make assertions on the responses received when running the requests and set variables that can be used by subsequent requests in the same file.

I am aware of two different, but very similar, HTTP file formats:

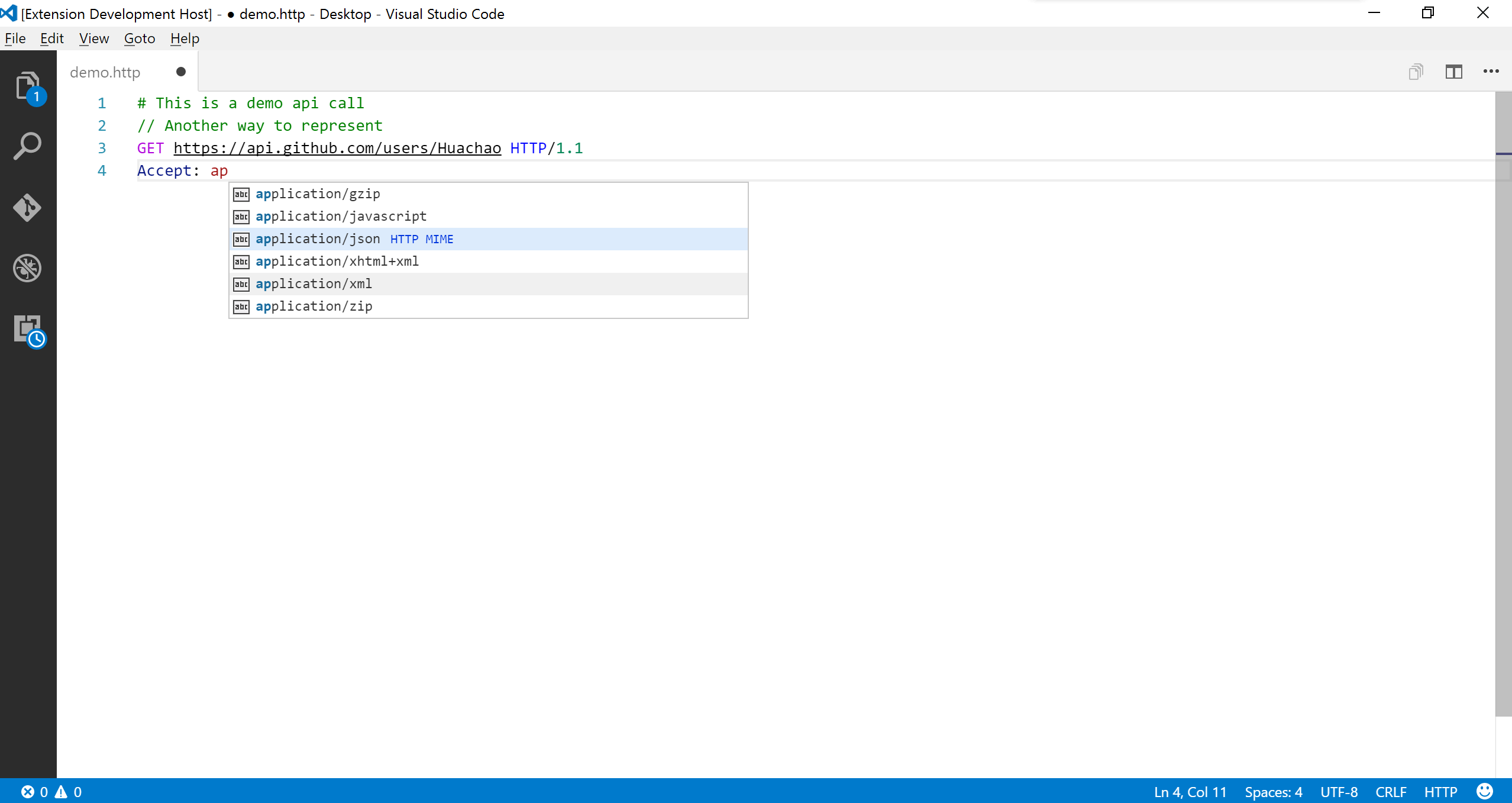

Both of them allow the developer to write HTTP requests with such niceties as auto-completion, error highlighting as you type, and color-highlighted HTTP response bodies where the content-type is known.

Think of this as writing HTTP “code” in your favourite IDE.

Incidentally: HTTP was originally designed to be used as an interface to distributed object systems. It is easily understandable and can be authored by hand without any help from fancy tools.

If you haven’t seen a HTTP file before, here’s a little sample taken from the VS Code REST Client docs:

GET https://example.com/comments/1 HTTP/1.1

###

GET https://example.com/topics/1 HTTP/1.1

###

POST https://example.com/comments HTTP/1.1

content-type: application/json

{

"name": "sample",

"time": "Wed, 21 Oct 2015 18:27:50 GMT"

}

This is extremely simple. Anyone with a little bit of knowledge of HTTP (which if you’re testing HTTP APIs, should definitely include you) knows exactly what this is doing. And best of all: this can be run both in the VS Code Editor and in IntelliJ IDEA Ultimate (and in the terminal or a CI, as we’ll see later), as their formats are fairly similar!

Contrast this with a GUI-based tool, where your knowledge of HTTP is almost useless as you have to learn yet another tool instead:

Unfortunately, Jetbrains has not made HTTP files support available in the Community (free) Edition, but hopefully with the competition from VS Code, they will make it available at some point (I have no idea if this is in the plans, I am just hoping it is, as it makes sense to me)!

Whereas the VS Code REST Client format has slightly more features than the Jetbrains format, only the Jetbrains format has support for testing, as of writing. Another point in favour of the Jetbrains format is that it has a specification called HTTP Request in Editor which I think is a great initiative. It would be amazing it this Specification could be used as the basis for a universal HTTP testing format in the future.

For this reason, I will focus on the Jetbrains HTTP file format to explain how HTTP files can be used for testing.

Testing HTTP APIs using the Request-in-Editor format

I want to make it clear that I am in no way associated with Jetbrains or have any commercial interest in advocating its products. My only relationship with Jetbrains is that my employer pays for IDEA licenses for all developers, including myself, so I might be considered as an “indirect customer”.

I think that the Request-in-Editor format (though it desperately needs a better name) is really the kind of thing that is perfect for testing HTTP APIs.

First of all, it uses the basic HTTP message format described by the HTTP RFC itself, but with a few additions to make it more easily authored by hand.

For example, a simple HTTP request can be represented by a simple URL:

http://date.jsontest.com/

Running this file should result in a single GET request to that URL. All you need to know here is that:

- GET is the default method if you omit it.

- HTTP/1.1 is the default protocol version if you omit it.

- The mandatory Host header is inferred from the URL.

So the complete HTTP request sent down the wire looks like this:

GET / HTTP/1.1

Host: date.jsontest.com

Notice that the URL scheme,

http, is not part of the request itself as it only establishes the transport protocol, and that due to HTTP’s age, CRLF is used as a line break.

I have no idea why programmatic HTTP clients and GUI testing tools think that this is too hard for testers to handle and try to abstract it all away. The “real thing” looks much better to me.

To illustrate a test, let’s implement in a HTTP file the same test that was shown in the Java example we’ve met earlier:

GET https://api.github.com/users/eugenp

Accept: application/vnd.github.v3+json

User-Agent: renatoathaydes

> {%

client.test('Given User Exists, ' +

'When User Information Is Retrieved, ' +

'Then Retrieved Resource Is Correct',

function() {

client.assert(response.body.login === 'eugenp');

});

%}

Simple, as it should be.

Notice that the original Java example did not actually set the

AcceptandUser-Agentheaders. The above example does because GitHub recommends doing so on all requests (andUser-Agentis mandatory now).

There are a few noticeable details in this example:

- the code to test a response is written immediately after the HTTP request, between

< {%and%}markers. - the code is written in JavaScript, ECMAScript 5.1 to be precise.

- there are a few built-in functions that can be used for testing.

- the

request.bodyis automatically parsed as JSON because of the response’s content-type.

The JavaScript API that can be used in these code snippets is documented in the IntelliJ Docs and can also be seen inline while writing the code in IntelliJ IDEA Ultimate (any Jetbrains readers: please make this feature available in the Community Edition!! This is not a “Enterprise” feature!), with auto-completion and all.

One more important feature of this format is that you can use variables and specify them both in response handle scripts and in environment files, which are written using JSON.

For example, you can create environment files, which must be called http-client.env.json or

http-client.private.env.json (to keep confidential data) that look like this:

{

"development": {

"host": "localhost",

"id-value": 12345,

"username": "joe",

"password": "123",

"my-var": "my-dev-value"

},

"production": {

"host": "example.com",

"id-value": 6789,

"username": "bob",

"password": "345",

"my-var": "my-prod-value"

}

}

And now you can use the variables in your HTTP files:

GET http://{{host}}/api/json/get?id={{id-value}}

Authorization: Basic {{username}} {{password}}

Content-Type: application/json

{

"key": {{my-var}}

}

You can also use JavaScript to set variables:

client.globals.set('my-var', 100);

Running Request-in-Editor files

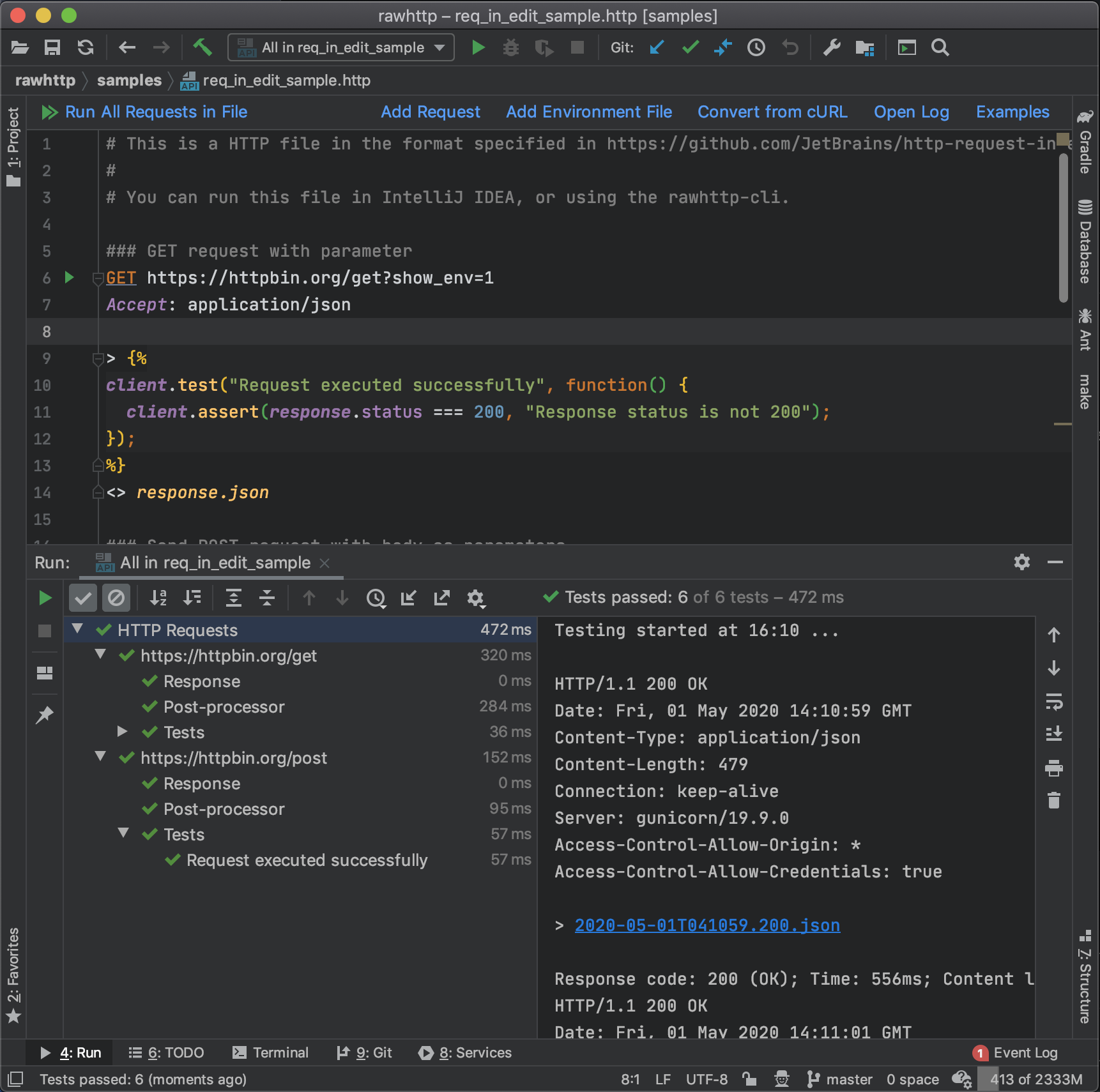

The easiest way to run a HTTP file in the Request-in-Editor format is, obviously, in IntelliJ IDEA Ultimate.

When you run it, it looks just like you’re running a unit test in the IDE:

Unfortunately, Jetbrains does not seem to have made a standalone executable to run such files… but I decided that this format is really cool and deserved a runner implementation that can be run by anyone with minimal overhead, so that you can benefit from writing nicer HTTP API tests and execute them in the command-line or in your CI, even if you don’t have a license.

So I wrote a HTTP file runner as a Java library, part of my own RawHTTP project, called rawhttp-req-in-edit.

I also added the run command to the RawHTTP CLI

so that you can execute any HTTP file that can run in IntelliJ.

Running a HTTP file now is as easy as running this command from the terminal:

rawhttp run my.http

If you want to specify an environment, pass its name with the -e option:

rawhttp run my.http -e development

The code is all open-source and published under the Apache 2.0 license!

I hope that this helps popularize HTTP files and that this becomes more widespread in the industry, because as the saying goes: we should use the appropriate tool for the job! And HTTP files seem to me to be the best tool for this important job.

Shortcomings of HTTP files

Even though HTTP files are great, I think there are some issues that need to be addressed for them to become even better.

Javascript response handlers

Even though JS is not a bad choice for this kind of small scripts, it would be great to have other choices.

Given how Java supports running quite a lot of languages, this limitation is probably quite easy to remove.

I might add support for other languages in my own implementation of the runner if there’s some interest. Please create a GitHub issue if you also would like that!

Related to that, the fact that Jetbrains uses an outdated ECMA version for this seems to be purely an implementation constraint. My guess is that they are using the deprecated Nashorn engine to run the JS code. With more modern engines, like GraalVM’s Polyglot framework, using modern JavaScript and other languages should be very easy.

Lack of declarative assertions

Just like writing HTTP in HTTP is better than writing HTTP in basically any programming language, writing declarative assertions in a HTTP-specific assertion language could be a very nice alternative to writing it in JS code.

For example, I have always wanted to be able to write something like this:

GET /resources/id-1

Host: mywebsite.com

### Expected Response

HTTP/1.1 200 .*

Content-Type: application/json

Content-Length: > 20

{{ body.id == 'id-1' ... }}

It would be awesome to write tests like this! We just need a HTTP-specific pattern language that is easy to write and understand, and flexible enough for most cases… where it comes short, we can still fallback on scripting.

But even though I enjoy implementing things, I don’t really have the free time and will to design something like this.

If you would like to do it, please get in touch! I might be able to help come up with ideas and would definitely try to help!

Buggy implementation

The IntelliJ support for HTTP files still feels a little bit like in Beta… there are a few obvious bugs that, when you start writing more advanced files, you might run into.

Hopefully, as this format becomes more popular, more effort will be put into making support for it better.

Conclusion

Testing HTTP APIs can be done in a much cleaner way than is commonly done today, and I hope that this blog post has convinced at least a few people that HTTP files are a great idea.

I hope to have sparked more interest in the development of an actual standard for writing such files, and that in the future, VS Code, IntelliJ IDEA, and other tools all converge on a single format as that would greatly benefit everyone.

Finally, even if the current situation is not ideal, you can already start using both VS Code and IntelliJ to write HTTP files, and if you need it, RawHTTP’s Java lib or its CLI to run HTTP files in the CI.